Innovation is one of those concepts with numerous definitions, that we come across on a daily basis in different situations. Many times, people and organisations make innovation into a value that needs to be the final product: “I want to be an innovator”, “I want an innovative product”.

However, if I could offer a definition on innovation that I believe to be appropriate, it would be “the capacity of generating perceived value”. Innovating would be, therefore, the ability to project something in an assertive and relevant way, reaching a person, a group of people or society as a whole. It represents a process that has human beings – and their necessities – as its central focus.

Through this spectrum, being an innovator is more than a final result, it is the capability of accessing human needs and translating them into something tangible, from a product to a new service, to solutions that could alter socio, cultural, economic and political patterns. It is up to the individual to define what scale they would like to innovate, but if they always start from a human-centred perspective, the impact of innovation will be potentialised every time.

On top of all this, if innovation is a process, it can be, consequently, systemised and put into practice by anyone that follows that system. Design, as a discipline and study field, tremendously contributes to innovation in this sense. By essence, Design – and designers – is always seeking for understanding of human behaviour – what do people say, feel, see, hear. etc. – in order to come up with a solution. Design is an empirical, experimental discipline that has for decades systemised – through practical learning – a process of extraction and understanding of human needs, generating innovation as a result.

Design’s proposition is a shift in focus when it comes to innovation

It proposes that, in order to innovate, people and organisations will have to expand their thoughts and stop looking for quantitative information only on their users and clients. As much as numbers can give you a sense of security, quantitative data can only give you answers you are looking for, but don’t necessarily translate what the clients are trying to communicate to you (font: Marc Stickdorn & Jacob Schneider, This is Service Design, 2014).

You can also simply chat with your clients, which would be, for sure, an enriching experience that will give you new perspectives on what innovation means to different people. A curious eye and an exploring spirit are a designer’s essence and experimentation is key.

What Is A Persona?

When you need to understand your client, the best way to do that is by speaking to them and understanding their necessities; an extremely important part of a designer’s job is field research. Through research, it is possible to detect behavioural and need patterns, which will give the designer a new perspective on the problem. The combination of this data becomes what we call a persona.

According to Stickdorn and Schneider, personas “are fictitious profiles many times developed to represents a specific group of people based on their shared interests. They represent a character with whom the design team and the client can get acquainted”.

This definition helps us understand two important points when building a persona:

1- It helps synthesise what was observed during field research, showcasing what characteristics, feelings and behaviours are the most important;

2- As it represents a person, it allows for empathy and helps to reach a satisfying solution.

Erika Hall offers another powerful definition: “A user persona is a fictional user archetype created by researchers on the basis of data gathered about the user group. User personas are useful for allowing designers to advocate for the users’ needs and maintain an empathetic, user-centred design mindset.”

Hall’s definition brings up an important point and a common mistake when building a persona: to assign to the persona characteristics that didn’t arise during research, showing that these characteristics most likely comes from the researcher’s biases. Well built personas are strictly based on extensive research data.

Building The Persona

In other fields, such as marketing, personas are created by grouping demographic data (age, place of residence, income, etc.) with personal history (education level, relationship status, etc). Although with this information we can put a persona together, we are unable to deeply understand what thoughts and needs that persona would have in real life.

In a design persona, patterns of behaviour are identified by understanding in which context your clients interact with your products and services. The focus is to comprehend what are people’s biggest pain points as well as their biggest motivators when interacting with a product or service.

Did I build my persona in the right way? Go through this checklist to find out:

- Personas should reflect observed behavioural patterns

- Personas should reflect on the present state (and not on a wish to the future)

- Personas should reflect what’s real, not what’s ideal

- Personas should help describe a solution path

- Personas should help you understand:

- The client’s context

- The client’s behaviour and needs

- The client’s challenges and conflict points

- The client’s objectives and motivation

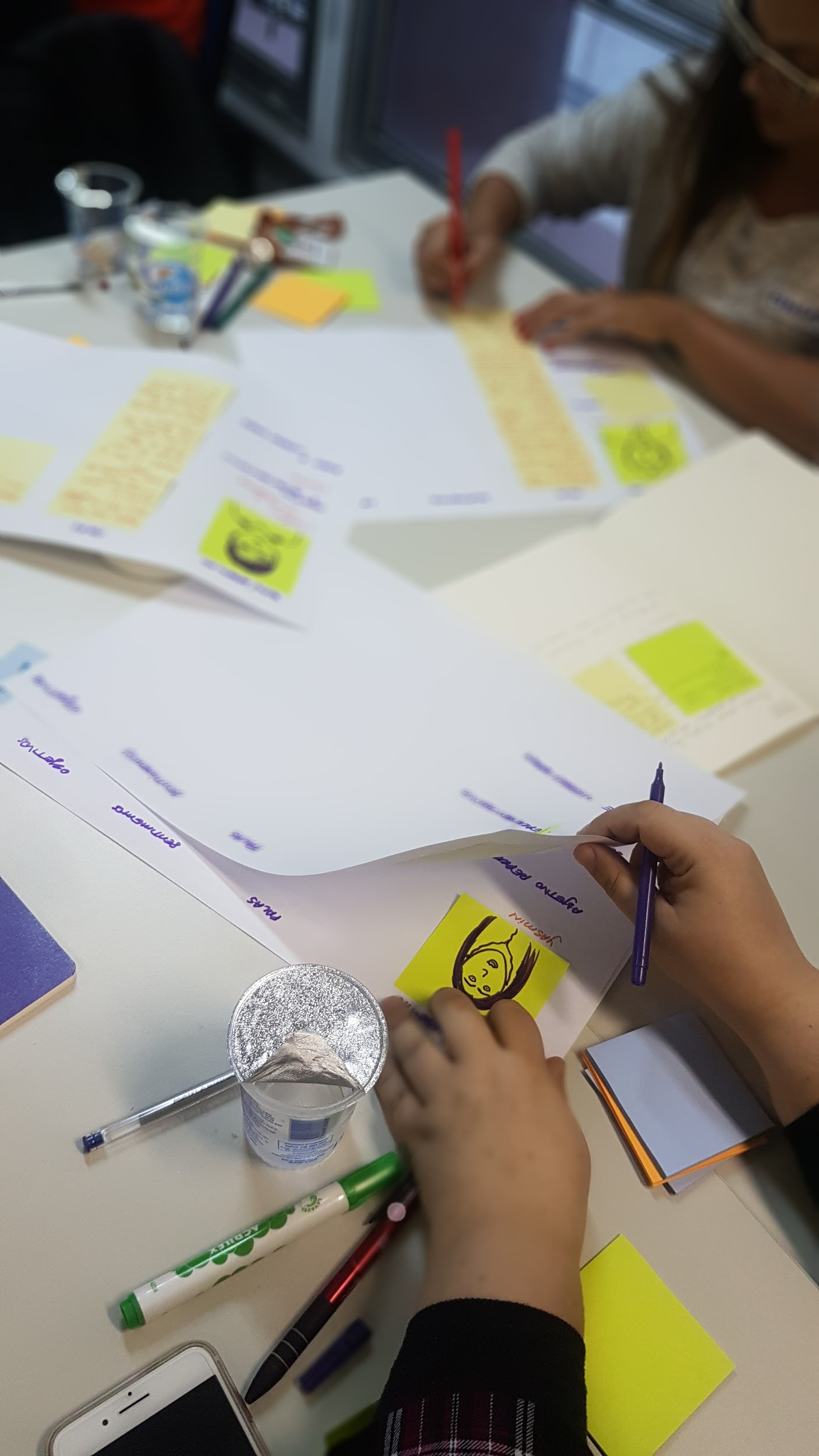

Ideally, personas are built in groups so that multiple ideas come together in order to validate what’s working and help fix what’s not.

The Advantages Of Build A Design Persona

Beyond accessing client’s behaviours and challenges, design personas can serve as a tool for companies to keep up with client’s behavioural changes and needs; they can help with the redesign of products, services, processes and, even, business models. The use of design personas will guarantee that you are always an innovation vanguardist.

Most importantly, since building personas is a people-centred process, the decisions will always come from what people need or desire.

—

If you’d like to start an innovation journey in your company, you can check out our in-house course offering as well as download for free our Design Thinking toolkit by clicking here.

If you’d like to see what are the upcoming courses in your region, visit our website.

If you have a special project and would like to use Echos’ consultancy services, you can send us an email.